We lived for three to four years in Caracas. We spent most of our time in the city, at work or driving to the nearby Caribbean beaches. This blog has many stories about our work life in the country. But what about the countryside? For work we did shoot commercials outside the city; but we were usually focused on our shoot.

In summer 1980, we were invited for a weekend by the daughter of an old Venezuelan family, with deep roots in Venezuela, to their cafetal (coffee plantation) in the state of Carabobo. Her family had occupied this coffee plantation since the days of Simón Bolívar. We went to see what Venezuelan country life was like.

Bolívar had been the owner of that valley and the hacienda which he had named for his Oath of Monte Sacro, the promise he made in Rome to free the South American colonies from their imperialist occupiers. In some ways, it represented the birth of the nation. We didn’t know the association or significance to this oath at the time.

Obviously, the family could say with veracity that “Bolívar slept here,” a claim made at many historic places in South America. Bolivar, El Libertador, freed six South American countries from the Spanish empire. It was a birth that inspired a continent.

The Cafetal was located northeast of Valencia in the valleys of the Litoral (Coastal) Mountains. It was about four hours drive from Caracas. Our group was our hostess and several friends from my wife’s work and my mother-in-law who was visiting us that week. We drove in two cars on the main highway and afterwards about another hour on an secondary road to a little village called Cariaprima. The coffee plantation was just outside the village. It was also a drive back in time to a more rural period.

Once upon a time, Venezuela was, as a country, one of the most important coffee producers in the world. It was also a leading cocoa producer. All that stopped when Venezuela became an oil producer. Pay for oil workers was much more than for farm workers and the work was easier. So people left their farms and headed off to the oil fields mostly around Lake Maracaibo.

As a result, there are many non-working coffee plantations in areas across the north of the country. Their design is more or less the same with a large stone plaza in the centre and buildings around that plaza.. The plaza wasn’t decorative, it was used to dry the coffee beans spread out there in the sun.

The old coffee plantation we went to had a few principal buildings situated around the central paved stone plaza. The main house and kitchen had electricity and a huge fireplace. This was located on the northern corner, with separate entrances around this plaza to stables, a chapel and the guest bedrooms. All part of the same structure.

Our designated bedroom had been converted from being a stable. The room was very quiet; it had a bed with sheets over a mattress stuffed with straw. The bedrooms did not have electricity and the nights were extremely dark with many shadows.

My wife was very afraid of a snake attack in the night; she saw snakes in every shifting shadow. That never happened, but she jumped up startled a few times during the night when she had nightmares of snakes attacking. We did not sleep as well as Bolívar.

We brought groceries for the weekend but the caretaker family that lived there and took care of the plantation had fresh food, many fruits and vegetables grown on the property waiting for us: mangos, guanábanas (soursop in English), limones Franceses (yellow lemons with a rough, bumpy skin), lechosas (red papayas), plátanos (plantains), cambures and titiaros (different types of bananas, large and small). We enjoyed these a lot. The plantation was almost self sufficient.

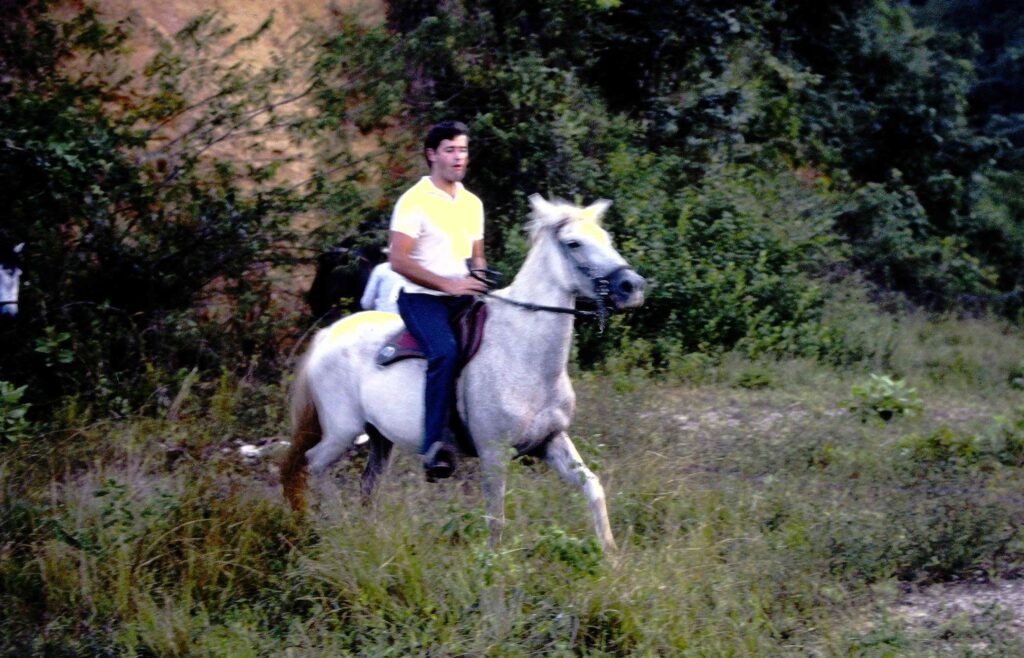

We enjoyed a pleasant evening around the massive fireplace. In the morning, we decided to ride horses a few kilometers across the valley to the hacienda also called Montesacro, owned by Nelson Rockefeller.

We had to pass through the little village in the valley to get there. A large group of people had gathered in front of a pretty, little church. They watched our little parade of young professionals pass by with some curiosity. We didn’t know why they were gathered, perhaps a baptism, a wedding or a funeral. Cycles of life. In small towns in Venezuela, the church has often been the centre and gathering place.

As we rode, we passed a cow in a field that was in the process of giving birth to a calf. We watched the calf drop to the ground then struggle to get to its feet. We rode on. Life goes on in the countryside; it is always a struggle.

Rockefeller was a rich aristocrat and colonialist from the US. He owned a lot of land. His principal interest here was mainly in raising horses. Venezuela in the 50s and 60s was like a colony of the US. The US interest was due to the oil and its exploitation mostly by US companies.

In the early 70s, the oil industry had been nationalized helped by the formation of OPEC. OPEC had been formed in the 1960’s by Venezuela and a few key oil producing Middle Eastern countries. It has since expanded to include many other countries. These countries felt they had been unduly exploited by the big petroleum countries. Juan Pablo Perez Alfonso, the Minister of Oil for Venezuela was one of the OPEC founders. He is famous for saying “Ten years from now, twenty years from now, you will see, oil will bring us ruin… It is the devil’s excrement.” He felt that money from oil would create greed, not good.

When we lived in Caracas, we knew many US and Canadians working for the nationalized oil companies. Caracas friends worked for these companies: Maraven (formerly Shell) and Lagoven (formerly Exxon). The nationalization took place over a long transition and seemed to be going smoothly.

Now, back on the trail to Rockefeller’s.

Nelson Rockefeller was no longer around or spending time in Venezuela because he had recently been appointed Vice President of the United States. It was a time when neither the President nor the Vice President of the US were elected. Both had been appointed to replace corrupt and crooked politicians.

Rockefeller had a long history with Venezuela. He had been an Assistant Secretary of State with responsibility for Latin America. He helped start a Venezuelan chain of supermarkets (CADA), invested in a dairy distributor and the Rockefeller family had many investments in the oil industry. He spent his honeymoon (the second, I believe) at this hacienda. As well, he was the Godfather of one of my Venezuelan clients.

When we arrived, we left our horses in an orange grove below and walked up the long driveway to the entrance of the house to see it. The hacienda was vacant. The house had a very beautiful view of the valleys to the north towards the Caribbean in the far distance. The north side of the house was all glass, pure windows.

The gardens had many flowering trees like bougainvillea and many others. Both the large main house and a guest house opened onto a sizeable swimming pool. It was a dream home.

One thing that really drew my attention was in the plaza on the north side of the house. Outside the windows was a breadfruit tree, with one enormous breadfruit. I hadn’t seen one before. We took some photos of the grounds and returned to our horses.

We had spent an hour or more walking around the estate before going back down the hill to our waiting horses.

Now after a couple hours of riding and an hour of waiting, the horses wanted to get back to their stables to eat and they began to trot, then gallop. When one horse starts to gallop, the others want to follow, even though we held on tightly to our reins and pulled hard to try to stop them.

The trees in the orange grove were not important to the horses, but they were for us riders. While the horses ran under the branches, we received quite a few whacks from the trees and the oranges above until we were able to slow the horses to a walk about a half a kilometer later. I had a few souvenir oranges in my lap.

My mother-in-law, as a large woman on an old smaller horse, didn’t have that problem. Her horse did not want to run, with good reason. After a few minutes, she slowly arrived at our group without any bruises or injuries from the branches or any oranges. It was just like Aesop’s fable about how slow and steady wins the race.

The routes back to the cafetal were through the woods. Past the community graveyard which looked very old. The old Venezuelan agricultural life on large plantations might also have been buried there.

We walked our horses slowly letting my mother-in-law’s horse keep up. This is not a region of highways or even main roads. There was nothing more than winding paths through the orchards. We had to find our way back to where we began. It might have been hard to find our way, but the horses knew. Today we hope Venezuela knows how to find its way as well.

The weekend was a complete adventure for my mother-in-law who had almost never been outside North America or to any rural areas. We saw countryside and the passage of time shown by the small sustainable farms to the plantations and then the abandonment of haciendas by colonialists.

Normally, we spent our weekends at the beach only an hour and a half from Caracas. One favourite beach spot was near Higüerote, which was recently bombed by the US during their invasion.

This trip to the interior was one of a kind. It was to yesterday’s Venezuela, but I think the countryside is pretty much the same today. It is quiet, with farmers and their small subsistence farms.

Even after Chavez was elected promising land redistribution and then became a caudillo (strongman). After years of US embargo and the economic difficulties that embargo caused plus the mismanagement of the economy by the Chavistas, promises never delivered, the country has suffered. Much of the emigration from Venezuela to other countries came from the cities. The campesinos (country people) stayed.

There are no Rockefellers in Venezuela anymore, nor many US people at all. They mostly abandoned the country under the pressure of US political opposition and embargoes; oil exploitation no longer possible. In any case, few ever went out into the rural areas. The extranjeros (foreigners) were busy working in Caracas or around the oil fields or mines.

This trip and many of our riding adventures closer to Caracas meant meeting and talking with local, very humble campesinos. On our beach trips, we stopped on the way back to negotiate with farmers to buy fresh fruits, mostly “hands” (what bunches are called in Spanish) of bananas particularly the small ones called titiaros. They were smooth and sweet. I enjoyed negotiating with the farmers who always had a sense of humour and time to joke around while trying to bargain for a higher price. I always thought that the socializing was more important to them than the sale. I hope that hasn’t changed.

Today, the Devil’s Excrement brings a new wave of greedy exploiters. Someone has to take a new Oath of Montesacro. None of the current players look like they really want to.

For more about advertising, visit Overcome AD-versity.