A freelance assignment in Hungary came up in 1989. The country was just breaking free from Russian domination and communism. A bank in Budapest, called DunaBank, wanted to launch a credit card. I was hired based on my marketing work with Texaco’s credit card operation, and the fact that Canada was less scary and more scalable than the U.S.

I flew over to Budapest for a few weeks to try to help. In Hungary, at the time, no one spoke English. I needed interpreters – linguistic and cultural. Few westerners and almost no western companies had arrived yet.

There was a generation of people there who believed if you had a good, it would be saleable, no matter what it was there would be someone to buy it. That was the new capitalism system. Supply was short, demand was strong. Therefore, selling a credit card should be easy. However, for some reason, no Hungarians wanted one. That prompted bringing in a westerner to see what could be done.

The bank wanted to market a credit card; but they had no idea what a credit card was. They had seen credit cards in all westerners’ wallets, and they knew these were little plastic cards. What they were unsure of was the mechanism by which these cards worked. They figured something out, but it wasn’t working. Almost all transactions at that time in Hungary were in cash, in forint notes, and individuals did not use cheques.

DunaBank had started a card, but as I learned quickly, it wasn’t a credit card. It was a debit card. Customers were required to deposit funds into an account with DunaBank to draw from when using the card. Enrollment was going poorly. I asked about card application forms and where they were distributed, thinking the more applications in people’s hands, the more cards would go out.

“We have almost all of the applications right here in the office,” was the reply. It was a supply-controlled economy. To get a card, people needed to know that the card existed, come into the bank and request an application. If the bank employee thought the person was qualified enough, then they would be given an application and asked for a deposit to go with it. Applications were only selectively given out. The completed application would be reviewed by the bank and potentially approved for the applicant in a couple of weeks.

My western view of credit card applications was to get as many applications into as many customers’ hands as possible. The more cards in circulation, the more value there was to having a card and the more places that would be interested in accepting them. Credit cards are something of a house of cards, the opposite of supply and demand. With credit cards, the more there are the more valuable each one is.

I had requested a meeting with the post office to understand mass mailing requirements before arriving in Budapest, presuming that direct mail would be our best starting point. When I arrived, I was told that the appointment wasn’t necessary because the post office was open every day for anyone. A cultural misunderstanding, perhaps. When I went into the post office, I learned there were no bulk mailing rates anyway and no one was doing direct mail.

Few merchants (all retailers were part of the government) accepted these Dunabank cards. So I wanted to learn why.

I spoke to leading retail chains, hardware stores, grocery stores, department stores, as well as car dealers. Many of the managers were apparatchiks appointed through their political alliances and didn’t know about market forces only operations, if they knew anything at all. All considered that if you had a good, it would sell. Given the scarcity of goods, they were usually right.

While driving around, I noticed a field outside of town that was mobbed with people, cars parked willy-nilly around it. I asked what it was and was told it was a market. More properly, a flea market. There were tables and blankets set up with all manner of goods on them. One table might have large jars of pickles. Next to it would be a stall with massive carburetors scavenged off some huge industrial truck. Next to that might be some needlework, or parts from a conveyor belt. People had come from the countryside and from nearby countries to sell whatever they could. Hungary was the potential source of foreign currency. I saw a group of husky Polish people who had driven for hours in a small Trabant (it must have been a clown car to get them all in) to try to sell whatever they had.

People had a rough idea about capitalism, but not a real understanding. A generation and more had learned that capitalists were lazy swindlers who could not be trusted. You might compare it with westerners’ understanding of communism; they are also lazy swindlers who could not be trusted. We are all the same, no matter the spin governments put on.

It was a steep learning curve, but Hungarians were individually very enterprising. Many had more than one job. Because all companies were in theory owned by the government, there was no conflict of interest in working for two companies that competed with one another and taking your knowledge from one job to the next. You needed a couple jobs, anyway, to afford to live well.

Life was certainly different. Hotels were almost non-existent. I stayed in the teachers’ union residence set up for teachers from outside Budapest when they visited the capital. There were book sellers on the sidewalks selling the latest novels and newspapers. Hungarian is a language isolate, not related to Germanic, Romance or Slavic languages, so people actively need to create their own versions of books and culture. Restaurants were excellent with dinner more Latin style, late at night with wine.

As one of the early westerners, I also got some advantages. I was able to attend the opera and symphony and met the Japanese conductor, Ken’ichiro Kobayashi, who was like a rock star. Our conversation was me in Spanish and him in Italian, with a few Japanese words I knew from growing up.

I also met some opera singers and was invited to a party at their house. Getting around was a challenge with no one speaking English and my Hungarian peaking at a couple hundred words. I would need to write addresses down for cab drivers because even the street number of my hotel was understandable to me as 326 but not as három huszonhat.

With the transition coming to a more capitalistic economy, I was interviewed on MTV (Magyar Television, not the music channel) and asked about the transition.

One area I touched was understanding company loyalty and the morality of it. It was a pretty odd idea when all Hungarian companies both compete and are commonly owned. I drew on P&G who market Tide, Cheer, and other brands of detergents to compete with each other. The people marketing Tide don’t tell the people marketing the Cheer brand what they are doing. It was a difficult concept in Hungary.

We did put together a marketing plan for DunaBank. It featured ads with the headline “Jobb, mint a pénz” which meant better than money, explaining the convenience of having the money you need when you needed it without a bulging uncomfortable wallet. We designed a program to hire students to deliver applications in neighbourhoods that might be more prosperous and more likely to be interested in having a credit card.

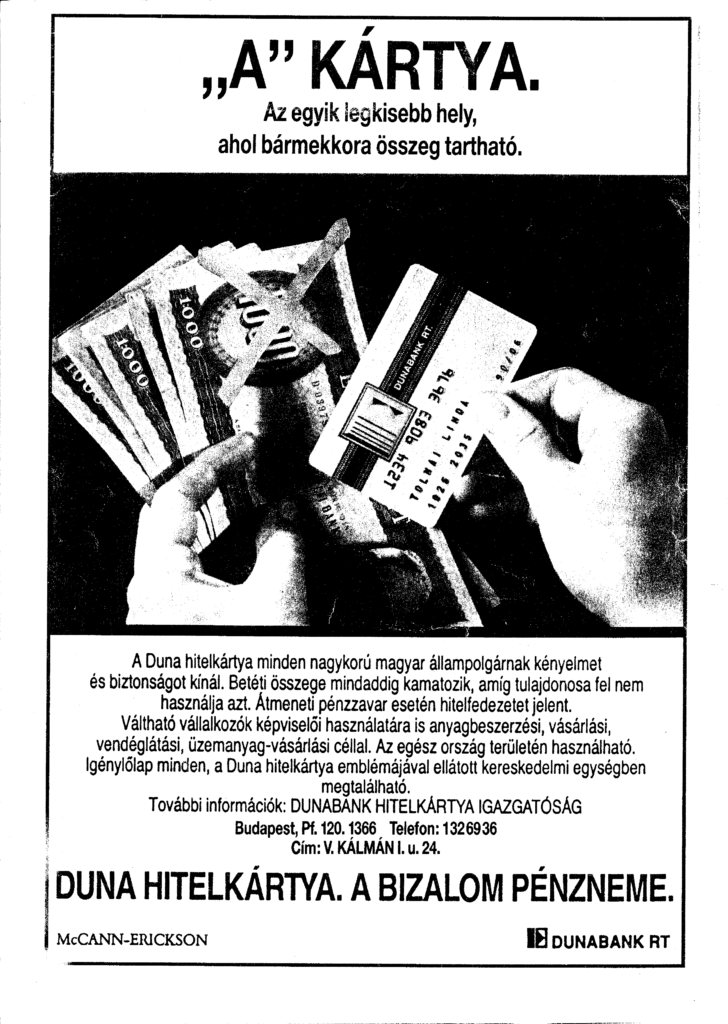

Here is an original concept layout before the final ad. The copy “a bizalom pénzneme” means “the currency of trust” for all you non-Hungarian speakers.

When we presented our Marketing Plan to the Bank, I think they were still dubious about giving application forms to people who might apply. The capitalist marketplace was not something people understood easily when control of supply was their basic assumption. This led to more cultural exchanges with Hungary for us.