You can be successful, and still fail. All it takes is a change in market conditions.

We were rewarded for excellent work with P&G on Ariel and Camay in Venezuela by receiving the assignment for the launch of Pampers. There was virtually no competition except old fashioned cloth diapers. How could we miss?

Pampers had an amazing track record of successes in virtually every country where the product had been launched. We had a budget for a major multi-media introduction – print, radio and television.

We traveled to Cincinnati to be briefed on how Pampers had been introduced in other countries around the world and how different cultures reacted to the new product. Procter & Gamble had amazing statistics and information on what had worked for successful launches everywhere. While usage rates varied from a high frequency per day in Japan to a low in Germany, we could see how Venezuela would fit on the curve. P&G had high sales volume expectations. We were ready!

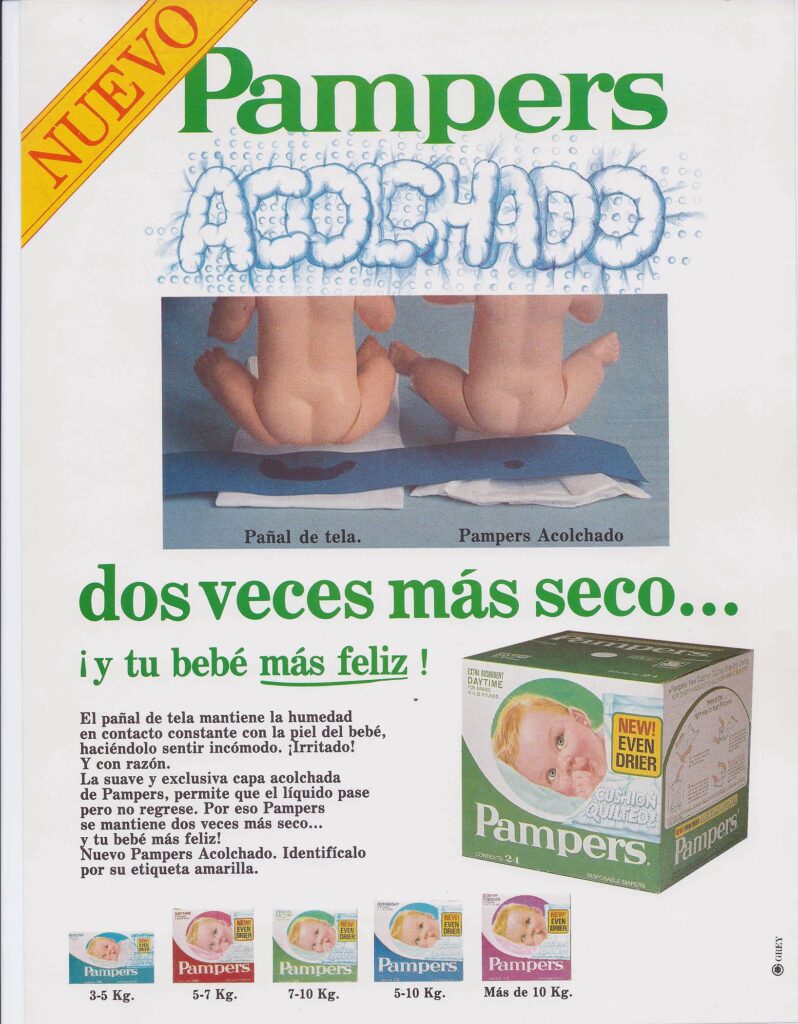

We developed our strategy, positioning Pampers as providing babies with superior comfort. This was because their little baby “pompis” (bums) would be kept drier and healthier thanks to Pampers’ absorbency which drew liquid away from their skin.

We felt it was important not to emphasize the convenience of use to mothers because mothers often felt guilty in switching to a more convenient alternative. Mothers already understood, in seconds, the tremendous convenience benefit – not having to clean dirty, poopy diapers every day, not having to keep a poopy bucket of used diapers, and not having to pin the cloth ends while a baby squirmed. We didn’t need to say it.

As discussed in Overcome AD-versity, convenience is one of the weakest of the four benefit classes to lead with.

Pampers is an unusual brand; it constantly needed to gain trial. Once the brand had trial, within a couple years it would lose that customer as their baby become potty trained. We would need to get that mother to try the product again if she had another baby. The brand was vulnerable to competitors every couple of years. Kids grow out of their diapers.

Our copywriter constantly seemed to have trouble saying the word “Pampers” replacing it with “Pams-per” – some consonant clusters are hard in other languages. She persevered through her frustration and our commercials were approved. The idea was to show a happier, drier baby in its Pampers. We were not allowed to show any real life bare bottoms in our print ads or demonstrations.

Shooting commercials where a baby cries on command or laughs on command was a major challenge. Remember W.C. Fields saying to never work with animals or children. Having worked with dogs, I was now ready to try working with babies. Neither one is intuitively very good at accepting instructions.

At the recommendation of P&G, we brought in a baby wrangler from the US to help cast for babies. She showed us how to make babies cry (cross their arms and legs) or laugh (blow in their faces). She helped us select babies brought in for a casting call by a long parade of proud mothers who all thought their babies were beautiful.

Our wrangler selected those who she thought would work in our commercial. The baby had to be okay being held by a strange actress in front of hot production lights while there was a crew of people on the other side of a camera. Cuteness? They were all cute. Who knew there was such a job as a baby wrangler?

Pampers already had some brand awareness since many Venezuelans bought the product on their frequent trips to nearby Miami, a favourite shopping destination, a 2-hour plane ride away. Consumers regularly brought back cases of Pampers from their trips.

We presented our plans to the Procter & Gamble Sales Force. This meant I had to do a 20-minute formal speech to the entire Sales Force, with videos, all in Spanish. Our Creative Director’s wife, Patricia, saved me by typing the full speech out on a copywriting machine in a very large font.

My Spanish was fine, but, like many English speakers, I would slip up on subtle tenses or genders at times and we wanted everything to come off perfectly. Rehearsals helped. Never be afraid to rehearse an important speech or presentation.

We launched with all cylinders pumping: TV, radio, print all doing their jobs. By most measures it was a very successful launch. We had covered all the bases.

After we got to market, a problem did come up. Pricing.

Pampers were priced based on importing product, initially, from the US, before committing to local manufacturing which would be a major capital expense. To import, P&G had to pay significant tariffs to the Venezuelan government on every box brought into the country. It was a smart idea to import to understand demand before committing millions to start manufacturing locally.

With the increase in consumer demand from our launch advertising, smugglers, including the Venezuelan military, were motivated to provide product for the Venezuelan Pampers market. They began immediately “importing” from Miami by loading product on military aircraft that were regularly going back and forth. The imported product landed in military bases and not through customs at the regular ports of entry. So, no import tariffs were being paid and added to the consumer cost of the product.

With a significant savings to the consumer from lack of tax and tariffs, the gray market product, fueled by this new channel of supply through the military, was easily undercutting the higher priced legally imported product that was tariffed. In no time at all, the entire market for P&G’s legally imported Pampers dried up faster than a baby’s behind. So did the opportunity to manufacture Pampers in the country.

Smuggling was our Achilles Heel and something we had not anticipated. It was a lesson in the vulnerabilities that marketing has from exogenous variables, things that happen outside your control. A change in government policies, an unanticipated competitive entry, the emergence of a virus, even a change in weather patterns, any disaster – these things can upset even the best laid plans.

In a little more than a year, P&G was out of the Pampers business in Venezuela. By then, I was also out of Venezuela.